How big can the Local On-Demand Economy get? We’ll be examining this question in several blog posts this week as we prepare for BIA/Kelsey NOW, which happens June 12th at the Mission Bay Conference Center in San Francisco. Use the discount code “MR100″ to save $100 on tickets. Will you be there?

BIA/Kelsey estimates that in 2015 the total addressable market for in-home on-demand services, including shopping time, travel and child/elder care, is 22.8 billion hours of currently unpaid household work, representing approximately 3.5 percent of total household work, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Time Use Survey. Using the reported average income of “1099 workers” from several sources of approximately $17 an hour, the total market this year, if fully engaged, could be worth up to $465 billion. At the current industry standard, a 20 percent share for the on-demand marketplace operators who connect customers and contractors, on-demand companies’ revenues potentially could be worth $93 billion in 2015.

We believe 2015 actual market penetration by on-demand companies appears, based on reported and leaked revenue data from various on-demand companies, to be approximately $18.5 billion, or 3.9 percent of total addressable market. Much of that revenue is captured in transportation, particularly by Uber, which is expected to book more than $10 billion in ride revenue in 2015. Note that Uber ride revenue includes drivers reported 80 percent share, giving Uber total fees of approximately $2 billion this year.

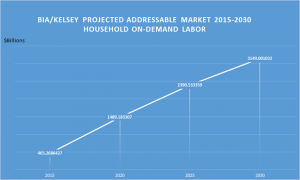

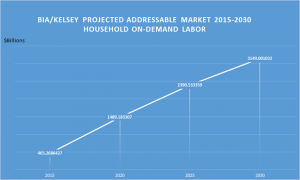

In short, there is 96.1 percent of a market unclaimed and it will grow at a compound annual rate of 13.50 percent through 2030 based on projected population growth and an increase in average on-demand earnings of 2.33 percent per year over that time, from $17-an-hour to $24-an-hour.

For now, Uber represents more than half of the revenue of organized 1099 labor. Much of Uber’s revenue comes from business travel, which is not included in the home services market, but it does claim considerable personal travel in cities where it is well known. Its rapid ascent suggests that similar growth could occur in any area where people have access to ad hoc networks of people and resources. Many of the carpools, childcare arrangements, cooking and helping services provided by neighbors to neighbors will be ingested into the formal economy through LODE organizations.

The household services market

Billions have been invested in home services companies in pursuit of work currently performed in the home by household members. In-home services, such as TaskRabbit, HomeJoy and InstaCart, cannot generate revenue if their offerings are too expensive for middle class households to replace with more profitable work in or out of the home. Affluent households can add these services at will, but their adoption of on-demand services will not deliver substantial economic growth, because workers must be able to afford to do contract work while substituting for their unpaid labor at home if there is to be a thriving market for local experience and services.

BIA/Kelsey Projected Addressable Market 2015-2030: Household On-Demand Labor

The rhetoric of LODE paints a vivid picture of on-demand workers busily exchanging services, sharing burdens while doing the jobs they most enjoy — it’s a promise on-demand companies are making to their prospective contractors. For example, a car to take the kids to school cannot cost $17 an hour for a mother making $12 an hour working at another task as an on-demand worker. If LODE home service workers are expected to adopt on-demand services as well as provide them, their earnings must exceed the cost of doing their own work at home.

The U.S. economy produced $16.77 trillion in GDP during 2013, the last year for which complete data is available. However, the calculation of GDP does not include unpaid household work. If it did, U.S. GDP would be several trillion dollars higher than it is reported today. Organizing this labor to bring it into the formal economy at a reasonable price with reasonable wages is the challenge to LODE companies if they expect to profit. That cannot be done while strangling the golden goose of ad hoc skilled and low-skilled labor with lower wages. Ultimately, both unpaid household labor and the work that can be exchanged for other services are essential to the economy, its time we counted both.

Household labor projections, 2015 – 2030

BIA/Kelsey has developed a model for projecting the addressable revenue in the home based on the householder’s ability to pay for services that they may forego doing themselves to make time for paid work in another area of their expertise. With reasonable and rising wages, household on-demand work can add up to $3.1 trillion to the U.S. economy by 2030 simply by formalizing transactions.