Scoping the On-Demand Home Services Market: Women In the Lead

TaskRabbit, HomeJoy, HomeAdvisor, Handy, ClubLocal, Pro.com, Amazon Home Services and, most recently, Google, to name just a few, have entered the exploding home services market to provide in-home labor and professional workers fast access to their local market. According to a recent The New York Times article, the market is valued between $400 billion and $800 billion annually by the companies chasing this newly accessible revenue.

With that massive revenue target in mind, BIA/Kelsey is in the process of segmenting and understanding the keys to the home services, research we’ll be introducing at our upcoming NOW: The Rise of the Local On-Demand Economy Conference on June 12th in San Francisco. In this posting, we’ll discuss who the primary customer targets for these services may be. In upcoming installments, we’ll look at when potential buyers will be most ready to pay for work that has traditionally been “free.”

Of course, in economics, nothing is free, but many factors are often very poorly measured or simply ignored when talking about the value of labor in the home. With the arrival of logistics systems that aggregate supplies of labor for the home, many new costs and expenses can be included in the economic decision-making of the household. That expansion of measured labor will certainly change the perception of the work that homemakers and home repair enthusiasts have previously treated as “free labor.”

Building a paradise or hell?

Logistics and information technology has dramatically improved productivity in large enterprises. They can transform local services, too, if entrepreneurs take the time to assess their customer’s needs and ability to pay in relation to the value of work that traditionally has been treated as contributions to the family.

What’s the real opportunity, to provide services to wealthy homes or to make home services affordable for many more people than today? Home services are often dismissed as a San Francisco-bred phenomenon brewed from a mix of overpaid Millennials and under-employed local workers who will take the lowest possible wage, because they have no other options. In reality, the emerging home services market is the product of enhanced coordination and logistics made possible by technology.

The arrival of data-driven coordination and management could result in an inhumane system of exploitation in which workers fight for scraps or it can lift more people into work that serves their neighbors, their own goals and those the community values. Only the latter approach can result in a robust local economy.

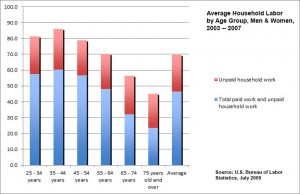

The average U.S. household headed by an adult reports it consumes 23.3 hours of unpaid household work a week (for purposes of this analysis, we exclude 15-24 years from the age distribution, as they have different household maintenance requirements). Men and women contribute significantly different amounts of this “free” but economically productive work.

The average U.S. household headed by an adult reports it consumes 23.3 hours of unpaid household work a week (for purposes of this analysis, we exclude 15-24 years from the age distribution, as they have different household maintenance requirements). Men and women contribute significantly different amounts of this “free” but economically productive work.

During their peak earning years, adults report substantially higher amounts of time spent on paid and unpaid household work in their homes, peaking at 60.2 hours per week between 35 and 44 years of age and declining to 23.6 hours for seniors older than 75. The volume of home services consumed is closely tied to the demographics of the home, with children and work, in particular, adding to the labor required to maintain the home.

Adults between 25 and 34 years of age report a spike in the total paid and unpaid household work they contribute compared to younger people (teens and young adults). Household labor increases by 91 percent, to 23.8 hours a week on average, with the arrival of children and a career. Between ages 35 and 44 years old, the average household requires 25.8 hours in unpaid work. People in these age groups report working 57.6 and 60.2 hours a week on average, respectively.

Women, however, report performing twice as much unpaid household labor as men in their late 20s and early 30s. Between 35 and 44, men take up somewhat more unpaid home work, providing 18.3 hours a week on average, but still only 55 percent as many hours as women, who turn in an average of 33.1 hours a week in unpaid labor for their household.

Welcome to the Women’s world

Women have been part of the formal workforce for less than 100 years, though their efforts have probably always been greater than men, who set the model for household history when they returned from the hunt, dropped the kill for the women to prepare and got to loafing around the fire until dinner was ready.

The first clear finding of our LODE research is that women are the primary consumers and providers of many of the services that will be swept into the on-demand market. They have traditionally controlled more of the consumer spending in the home, and now will be counted as providing most of the in-home productivity. That’s not to say that men are less likely to pay for household help than women, but it is necessary to underscore the different calculations made about household labor by women, who view spending money for in-home labor as a direct trade-off with expending their own free time on behalf of their family.

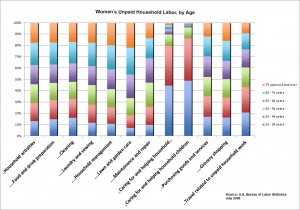

Figure 2 shows the breakout of unpaid household labor performed by women. At every age, adult women have a great deal to do to maintain their home, with the share of time dedicated to caring for children or aged parents between 25 and 44 years of age. At that time of life, all other facets of unpaid work are sidelined. General household activities, food preparation, cleaning, laundry, shopping and food shopping are shoved into spare moments. In fact, almost 90 percent of their time at home is spent on caring for children or others in the home. Driving for the household remains primarily Mom’s responsibility, too.

Men do take up much of the child-rearing burden, but surprisingly 25- to 44-year-old men do more non-food shopping than women, suggesting that personal shoppers will be increasingly important to time-starved parents. Except for the increased childcare and shopping responsibilities in their 20s to 40s, men’s share of unpaid household labor remains relatively stable throughout life. They spend roughly the same amount of time on cooking, cleaning, bookkeeping and doing lawn work (the area most dominated by men) throughout their lives.

On-demand vendors should recognize that women have already mastered time-sharing and cooperation to manage their household responsibilities. They’ve split time with other mothers and care-givers (for children and adults living in the home) and traded breaks in their day with other women, taking kids from a neighbor or friend to give them time off from mothering. Likewise, cooking and food preparation is traditionally a communal activity that can be shared, and it is natural for women to cook one or two days a week in trade for food prepared by others the rest of the week.

Novel combinations of payment and volunteerism — coordinated by a LODE vendor, who profits from revenue paid by customers who cannot spare time — will support significant networks of community labor, largely on the model pioneered by women who worked together to make their contributions to home and city. Not all work managed by a LODE vendor must be paid, it merely needs to contribute to a profit to be viable.

Given that women already spend almost twice as much of their non-workplace labor on household tasks than men, they will be drawn to on-demand services with the same care and fierce protectiveness that makes women successful mothers, CEOs and employers today. They are accustomed to the calculations that make “part-time” labor add up to a good life. On-demand vendors will benefit from studying the way women use their time at home and work, as well as how they negotiate the division of labor.

This is an excerpt from an upcoming BIA/Kelsey report, which will be presented in full at the NOW Conference in June.